CLEVESCENE.COM

Recycled Blues

Alabama Sky is somewhat brighter the second time around.

Blues for an Alabama Sky Cleveland Play House, 8500 Euclid Avenue Through March 11

216-795-7000.

Presented by Pittsburgh Public Theater at the O’Reilly Theater, Pittsburgh

Through March 4

412-316-1600

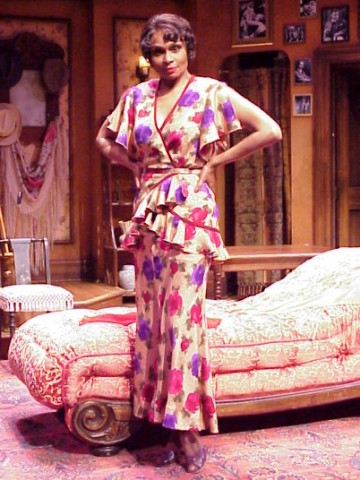

Vivian Reed and Alvin Keith in Blues for an Alabama Sky.

Pearl Cleague’s Blues for an Alabama Sky defines the term “potboiler.” The play takes its five characters through so many trials and tribulations that, to paraphrase a Thelma Ritter quip from All About Eve, “there’s everything but the bloodhounds yapping at their behinds.”

Cleague attempts to capture a desperate Harlem as it evolves from jazz playground to Depression wasteland. When this work played Karamu in a catatonic production in May of ’99, the experience was like night duty at the House of Wax.

Now it has been dug up from a too fresh grave as the Cleveland Play House’s contribution to Black History Month. Given a lush budget and far more loving care than it deserves, it has been resuscitated to a life it previously lacked. The theater has imported an expert cast of prestidigitators, who can make moribund clichés fly like little pink cupids. Skillfully jazzed up by Chuck Patterson’s sizzling direction, it now offers the fun of a so-bad-it’s-good MGM movie from the ’50s. Specifically, with its Lorelei of a heroine wreaking havoc, devouring men’s souls, and forever singing a sultry blues dirge, it brings to mind one of Hollywood’s tarted-up desecrations of Faulkner.

Cleague’s characters are stamped-out paper dolls. There is Guy Jacobs (Stanley Wayne Mathis), costume designer of the Cotton Club. He is desperately trying to design gowns to catch the eye of Paris diva Josephine Baker so he’ll be whisked out of hard times and straight to gay Paree. Due to the demise of censorship, he no longer has to hide his attraction to men, but the arched eyebrows, sassy bon mots, and limp wrists are vintage Tinseltown pansy. Mathis does his best with an offensively clichéd role.

Angel, a fading, just-fired chanteuse of the Cotton Club, is played by Vivian Reed, an actress who specializes in playing red-hot mamas in shows like Bubbling Brown Sugar. Without Reed, this character would be another plaster-of-paris floozie in a long line that stretches from Jezebel to Carmen Jones. Yet Reed, in the tradition of Lena Horne and Eartha Kitt, is a torch singer whose flame never wanes. Her intense musicality brings scat and rhythm to the most mundane piece of dialogue. Giving a performance that’s a cornucopia of growls and purrs, she turns Cleague’s dross into leopard skin.

Also in attendance is Delia (played winsomely by Kena Tangi Dorsey), Angel’s Pollyanna of a next-door neighbor who campaigns for birth control, and Sam Thomas (Wiley Moore), a good-hearted doctor who performs illegal abortions. Finally, there is Angel’s dangerous Alabama suitor, Leland Cunningham (Alvin Keith).

The play takes us into August Wilson land, where descendants of slaves break into factions — some wrapping themselves in old-time religion, others embracing the syncopated temptations of urban life.

When these two factions come together — as when the Alabama farmer takes up with the capricious torch singer — lives explode like colliding meteors. What would be gripping in a well-edited two hours becomes exhausting in two hours and 45 minutes (including a tiresome number of blackouts).

Famous names, such as Langston Hughes, Margaret Sanger, and Adam Clayton Powell, are dropped every few minutes for obvious period effect. It’s a vinyl variation on Chekhov’s Three Sisters, with everyone unfulfilled and yearning to be somewhere else.

Where Wilson has a way of turning his characters into brooding totemic firebrands speaking a rich poetry, Cleague’s figures seem to speak in pamphlet argot. A great cast can do only so much with such purple prose.